Does organic matter matter?

Review of the article “Highly decomposed organic carbon mediates the assembly of soil communities with traits for the biodegradation of chlorinated pollutants”

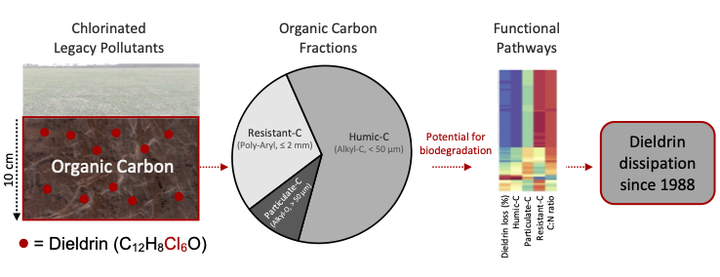

Graphical abstract reused with permission from Elsevier (23.11.2020).

Krohn, C., Jin, J., Wood, J. L., Hayden, H. L., Kitching, M., Ryan, J., Fabijański, P., Franks, AE., Tang, C. (2021). Highly decomposed organic carbon mediates the assembly of soil communities with traits for the biodegradation of chlorinated pollutants. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 404, 124077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124077

Disclaimer: I am an author of this paper. You can read the abstract here.

Why read this article?

It explores how soil organic matter of two Autralian soils in Victoria related to the microbial ability to break down one of the organochlorines, called dieldrin. Thanks to the thorough work by officers of Agriculture Victoria the authors had access to dieldrin concentration in fenced paddocks from 1988 - which is really rare.

The fencing had hardly moved since that time which means the analysis was based on how much dieldrin had actually dissappeared in each of the paddocks and found associations of this total dieldrin loss with microbial diversity and organic matter measurements. Ultimately it may help to understand better what makes dieldrin disspappear more.

What were the main conclusions?

One of the two soils was clearly ‘better’ at making dieldrin disspappear.

And as it happened, that was the soil which contained organic matter which was more decomposed (based on comparing three different carbon fractions) and hosted microbes with a greater potential to degrade aromatic and chlorinated materials.

It was speculated that the abilities to break down organochlorines were the result of microbes that had to adapt to poorer food quality, i.e. carbon sources, over the last 30 years. These so called resource-limitations may favour a ‘high-tech’ slow-growing microbe, with greater and more refined abilities to degrade stuff, rather then those fast-growing ‘bully’ microbes that are greedy and grow well on simple food sources but then push all other microbes away.

What were its main limitations?

The statistical analysis was based on a small samples size and has low power. It requires further experiments and field surveys at larger scale to get more empirical evidence and confirm the speculations.

What does this mean for POPs?

Organic matter matters! But not the way you might think….

A potential outcome of this is that natural degradation of POPs could be indeed enhanced if we can encourage the ‘high-tech’ microbes to grow better or discourage the ‘bully’ microbes to grow.

It also means that soil that is of higher quality (i.e. less decomposed) is actually not great at breaking down organochlorines. Current soil health practices of no-till and perennial pastures might inhibit the break down of organochlorines.

In fact, frequent tillage might just be the thing that is needed as it would encourge the breakdown of fresh organic matter and once that is used up - it may enable the slow-growing high-techers to grow better.

What do I think about it?

Well, I am an author so… :). I think it contributes to a complex issue. Perhaps, it provides some guidances on how future studies can combine bioinformatics with classical soil sciences to explore complex interactions with contaminants.